Last week’s post on Chicken with 40 Cloves of Garlic got me

thinking, not about the dish’s qualification as an easy and heart-warming

post-holiday dinner (which was the point of the post), but about its claim to

fame: its legendary forty cloves of garlic. More specifically, I got thinking

about our contemporary love affair with garlic. Hard to imagine cooking dinner

these days without mincing up at least a few cloves of garlic. But this hasn’t

always been the case. Not, at least, for us English speakers.

When the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley traveled through Italy in

the early 19th century, he was horrified to learn that women—yes,

even women—ate the pungent little cloves. “There are two Italies,” he wrote

home; “The one is the most sublime and lovely contemplation that can be

conceived by the imagination of man; the other is the most degraded,

disgusting, and odious. What do you think? Young women of rank actually eat—you

will never guess what–garlick!” Nothing, to Shelley, could better illustrate

Italy’s degraded condition than the fact that its women ate garlic. Even

Shelley, iconoclastic romantic poet that he was, simply could not fathom

kissing a young woman with garlic-scented breath.

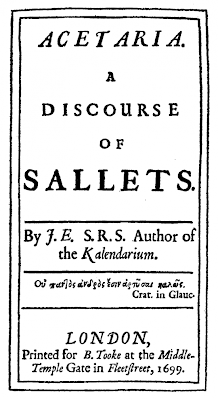

But then Shelley was simply echoing traditional English views voiced over a hundred years earlier by the gardener and diarist John Evelyn in his Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets:

Garlick, Allium; dry

towards excess; and tho' both by Spaniards and Italians, and the more southern

people, familiarly eaten, with almost everything, and esteem'd of such singular

vertue to help concoction, and thought a charm against all infection and poyson

. . . We absolutely forbid it entrance

into our salleting, by reason of its intolerable Rankness, and which made it so

detested of old; that the eating of it was (as we read) part of the punishment

for such as had committed the horrid'st crimes. To be sure, 'tis not for ladies

palats. nor those who court them.

Deemed inappropriate for young ladies’ palates (or for those who court them), yet force-fed

to criminals: such was the distaste in which garlic was held.

And yet, by the same token, it was also believed to be a

“charm against infection and poison”—which claim, by the way, has been

confirmed by modern medicine that has identified garlic’s strong smell to

result from the sulfur-containing molecule that results when cloves are chopped or crushed, thereby releasing the enzyme allinaise which converts the amino acid alliin into the smelly but antibiotic and antifungal compound allicin. Thus, whether for good or for ill, it's only when garlic is chopped, crushed, or chewed that it gives off the

powerful odor that makes your

breath smell—and your skin and blood as well. Apparently mosquitoes find the

smell unappealing and so don’t bite garlic eaters who are thus spared such mosquito-borne

diseases as malaria, dengue, yellow fever, and West Nile virus.

But mosquitoes are hardly unique in their dislike of garlic Just think

of vampires and their legendary aversion to it. If you want to protect

yourself against the likes of Count Dracula, you’d be wise to follow Bram

Stoker’s advice: rub garlic over your window sashes, door jambs, and around the

fireplace “to ensure that every whiff of air that might get in would be laden

with the garlic smell.” Take the further precaution of adorning yourself with a

wreath of garlic flowers around your neck.

Interesting, isn't it, that despite its medicinal properties—not to mention the protection it provides against blood-suckers of all shapes and sizes—garlic was nonetheless forbidden to young ladies. Apparently it was better they die of malaria or join the ranks of the undead than suffer the indignity of halitosis, or, in plain old English, bad breath.

Two final tidbits on the subject of bad breath. First, it was another pungent allium from which garlic derives its second syllable: the leek (gar was the Old English word for

spear; perhaps the long bladelike leaves of the garlic plant were thought to

resemble spears)—and bad breath was associated with leeks as well. According to

Isabella Beeton’s 1861 Book of Household

Management, “to prevents its tainting the breath, the leek should be well

boiled.”

The second tidbit brings me full circle back to my Chicken with 40 Cloves of Garlic. Since it's only when they're chopped, crushed, or chewed that garlic cloves release their odiferous fumes, by cooking them whole, one can enjoy their mellow, creamy sweetness with no ill effect.