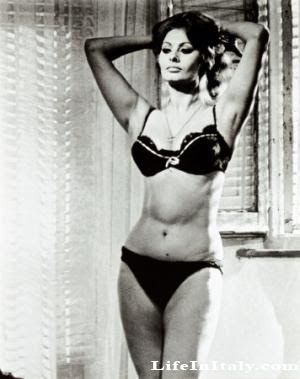

If there’s a person out there who doesn’t love pasta, I haven’t yet met him. Having raised two kids and having fed dozens of their friends over the years, I can attest to the fact that if it weren’t for pasta, America’s children might be in danger of starving to death. When all else fails, it’s macaroni and cheese to the rescue. And we never outgrow our love for pasta. Let’s face it. If you didn’t crave it so desperately, you wouldn’t have to torture yourself with those high-protein diets that deprive you of precisely the thing that put on the extra pounds in the first place. (And what’s wrong with an extra pound or two anyway? Just think of Sophia Loren, standing there in all her zaftig glory, declaring, “Everything you see I owe to spaghetti.”)

I remember reading somewhere that all a food magazine has to do to bump up sales is feature pasta on the cover. It doesn’t matter whether that pasta is spaghetti, fusilli, vermicelli, ziti, radiatori, farfalle, or lasagna, nor does it matter whether it’s been marinara’d, puttanesca’d, carbonara’d, alfredo’d or pesto’d. All it’s got to be is pasta and the crowds come running, forks at the ready.

Funny, isn’t it, that we should be so utterly helpless to resist what, when all is said and done, is no more than paste, which is, of course, a related form of the same word. Paste: “A liquid adhesive made by mixing roughly equal portions of flour and water and heating it until it thickens, used since ancient times for book binding, decoupage, papier-mâché, and for adhering paper to walls.” Replace the water with egg, and what do you have? Homemade fresh pasta. It’s not surprising that one way to test whether the spaghetti’s done is to hurl a piece against the wall: if it sticks, it’s done. By this logic, you could use al dente pasta the next time you set out to wallpaper your kitchen.

And then there’s pastry, which turns out to be just another form of the same word. Whether it’s shortcrust, flaky, puff, or choux, our pastry, the historians tell us, evolved from ancient Mediterranean filo-type doughs, made by mixing—guess what?—flour, water, and a bit of oil into a dough and stretching it into paper-thin sheets. Puts me in mind of a cartoon I’ve got over my desk. Crusaders are returning from the Holy Land, their javelins incongruously skewered with pineapples, bananas, and loaves of bread. The caption reads: “By the time we got there, all we wanted to do was raid their kitchen.” There’s truth said in jest: the Crusaders might have left Europe with the dream of winning back the Holy Land, but it was with enticing new foods they returned, including the ancestor of the delights we gaze at so longingly in the windows of French patisseries today: the Napoleon (aka the mille-feuille, or “a thousand leaves”), the cream puff, and the éclair.

Pasta. Paste. Pastry. Hard to believe, isn’t it, that a simple homely little mixture of flour and liquid could be so irresistibly good?

[NB: Here's a confession. I've had that cartoon, from The New Yorker, over my desk for years, believing the whole time that the figures were returning Crusaders. I just looked more closely. I was wrong. They're Vikings. Hmmm. On the other hand, if I remember my history correctly, the Normans were originally of Viking stock—Norman means "Norseman"—and the Normans were Crusaders, so maybe I wasn't so wrong after all. Phew.]

[NB: Here's a confession. I've had that cartoon, from The New Yorker, over my desk for years, believing the whole time that the figures were returning Crusaders. I just looked more closely. I was wrong. They're Vikings. Hmmm. On the other hand, if I remember my history correctly, the Normans were originally of Viking stock—Norman means "Norseman"—and the Normans were Crusaders, so maybe I wasn't so wrong after all. Phew.]

I am always tickled by the fact that the related terms in Spanish tend to trip me up. The feminine noun is "pasta," (paste) but the masculine noun, "pasto," means pasture, grazing or fodder. So whenever they describe cows grazing, it conjures up images of cows eating spaghetti. I made a worse mistake when I read bits of the Iliad in Spanish for the first time. The opening lines speak of the dead bodies being food for scavenging birds, but I was thrown momentarily when I lazily read "pasto de aves" and thought it was an odd dish that I couldn't remember ever reading about in the English version!

ReplyDelete