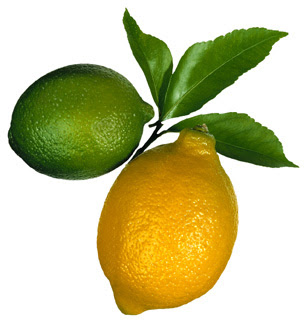

A guy walks into a bar and orders a Corona with lime. No

problem. He’s gets his bottle, icy cold, with a wedge of lime stuck in the top.

That would be the small green citrus fruit that goes by the name of lime. At least that’s the name it goes

by here in the United States. That’s why we call the color “lime green.”

Because around here, limes are green.

By the same token, in these parts, the larger yellow citrus

fruit is a lemon. That’s why we call

the color “lemon yellow.” Because to an English speaker, lemons are yellow.

But go south of the border and order what you think is the exact

same drink in Spanish—“una Corona con

lima”—and you’ll get your icy cold bottle of beer but now it’ll be adorned

with a wedge of lemon.

In lots of Spanish speaking countries—in Mexico, Venezuela, El

Salvador, and the Dominican Republic, for instance—the small green citrus fruit

we call a lime is known as a limón,

while the larger yellow one is a lima.

Aunt Clara, of Aunt Clara’s Kitchen,

a delicious blog of traditional Dominican recipes, tells me that in the Dominican

Republic, lemons are sometimes even referred to as limónes amarillos, or “yellow limes.”

On the other hand, in Spain itself, the mother country as far as

Spanish is concerned, limas are limes

and limónes are lemons. And get this

one: in Portugal, a limão is yellow

and a lima is green, but in Brazilian

Portuguese, it’s exactly the reverse.

Why all the citric confusion? What happened during the

transatlantic crossing?

As with so many fruits, the confusion is the result of a lot of

history, a lot of meandering, a lot of hybridization, and a bit of climatology

as well. In the case of citrus fruits, the story begins in the part of

Southeast Asia bordered by Northeastern India that’s the original home to both

the lemon and the lime. Citrus trees hybridize easily, so it’s hard to know

what was what, especially given the linguistic confusion involved back then. Ancient

Indian medical treatises use the word jambiru

(which you can still find in Ayurvedic sources), but it’s not clear whether

lemons and limes were meant. The Hindi word nimbu

is usually translated as lemon, although it might have referred to lime as

well, and it appears to be the source of both words. How did nimbu become “lemon,” you might wonder?

According to linguists, when the “n” in nimbu

is “denasalized,” it sounds like an “l” (you can ask your linguist friends

about this one), which is precisely what happened to transform the word into

the Persian “limu” and the Arabic laymûn from which the European languages

got their various citric vocabularies since there was no

native Greek or Latin word for any citrus fruit. [Citrus itself, in case you’re wondering, comes from the Greek word

for cedar, κεδρος kedros, perhaps

because of a similarity in smell.]

So was the fruit that grew back then in northern India and

Southeast Asia yellow or was it green? It depended on the variety planted,

natural hybridization, and even on the weather—as it still does. When winters

are warm, citrus fruit remains green, but if the temperature drops, the fruit

changes color as it matures.

When citrus reached the New World in 1493, certain varieties

took better to subtropical regions where the cooler winters turned the fruit

yellow, whereas in the hotter tropical regions, the fruit remained green. In

both cases, the staple citrus was known as “limón.”

“Lime,” for whatever reason, was reserved for the less important member of the family,

whether that country cousin was yellow or green. The lime barely registers in cuisine

north of the border, and the lemon rarely plays a starring role in Hispanic

cookery.

Which is why when you ask for a Corona with lime in the US, you

get a wedge of green fruit, but unless you like lemon in your beer, remember to

order “una Corona con limón” when you’re

south of the border. Or at least specify “lima

verde.”

Thanks for the kind words & happy holidays!

ReplyDelete